Happy New Year, by the way. I guess. I'm not feeling too optimistic about it, myself. But anyway!

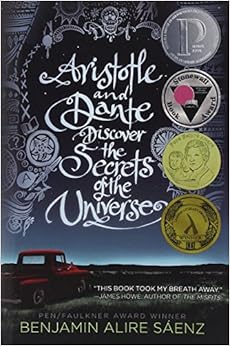

Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe got a lot of buzz from blogs and BookTubers alike. So when I saw it at the library (when I went to return The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, actually) I figured I'd give it a shot. I mean, look at that cover. Look at all of those awards!

|

| Image courtesy Chloë Foglia and Simon & Schuster |

Well, that's not entirely true. I liked most of the book as much as everyone else did—I just side-eyed the ending.

This is something that came up for me in Nimona as well: both stories feature a close friendship between two male characters that are intended by the author to be read as romantic. It's a little more explicit in Aristotle and Dante, obviously, but Noelle Stevenson has gone on record saying that Goldenloin and Ballister are absolutely canon.

And while, you know, hooray for representation, I'd like to take a moment to talk about how The Patriarchy Hurts Men Too. In this instance: we don't allow men to have emotional intimacy and vulnerability with other men without it immediately being read as romantic/sexual. I was gunning for Aristotle being straight (or, at least, not into Dante) the whole time. Not because I don't want stories about queer characters, but because I think a story about men being close friends is really important right now. Yeah, we have lots of models of scary-adventuring-heroes best friendship, but that's not friendship looks like for most kids. Where are the models of everyday emotional connection between men? Without the "no homo" punch line?

Never mind being a boy who has a gay best friend—how many gay men hesitate to come out to their male friends because they don't want to jeopardize the friendship? How many gay men are in love with one of their male friends who will never love them back—it would be nice to have models or roadmaps or at least stories about how other people dealt with that situation. Even fictional people.

But beyond my frustrations with representation, the whole ending felt rushed and too neatly tied up. The conversation that Ari's parents have with him about how they ~~just know that he's in love with Dante and how he should be brave and admit to himself is very deus ex machina, I don't care how many gay sisters Ari's mom has.

And finally, some factual nitpicking I didn't think of until I sat down to write a review: in a story about two gay (or at least bi?) teenage boys in the 80s, how is there no mention of AIDS? Things started blowing up in 1981, and And the Band Played On was published in 1987. Surely either Ari or Dante or someone around them would mention it, at least offhand? But I don't think anyone ever does. (Feel free to correct me on this point! I'm relying on memory here.) Did people in El Paso just not talk about AIDS in the mid-80s?

Everything else about the story is on point. Sáenz is a fantastic writer and he nails the very tricky problem of managing a teenage protagonist's voice perfectly. Ari is up there with Holden Caulfield: the right balance of insight and thoughtfulness with naivete.

No comments:

Post a Comment