I finished this book over Thanksgiving weekend and I don't know what to say about it.

I finished this book over Thanksgiving weekend and I don't know what to say about it.When I wrote my undergrad philosophy not-a-thesis on artificial intelligence and the moral worth of Rachel Rosen, one of the sources (I think it may have been The Mind's I) mentioned Lem's The Cyberiad. For all of my reading and sci-fi enthusiasm, that was the first time I'd ever even heard of Lem. I didn't know much more about him when I came across Solaris a couple years later, except that the name had stuck in my memory.

The edition of Solaris you're going to read in English is a translation from French, which was itself translated from the original Polish. I eagerly await the day a fresh new English translation from the original Polish hits the shelves, because I think the resulting language ends up rather clunky, especially in the descriptions of Solaris' fantastic shapes and displays.

But wait—that deserves a backtrack. Solaris is the story of a far-off planet, Solaris, that attracts attention from Earth scientists first because of its unusual orbit and then because of the giant, fantastic ocean of goo that covers nearly all of its surface. Specifically, the story is about Kris Kelvin's expedition there and what he finds. Kelvin arrives after the scientists at the Solaris research station decided to bombard the ocean with heavy duty X-rays. Now, as a result, all of the scientists on board are getting "visitors": neutrino flesh and neutrino blood replicas of someone haunting their past. Kelvin's visitor is his dead wife, Rheya. Perhaps they are a result of the X-ray bombardment, perhaps not; perhaps the ocean is trying to study its new inhabitants, or perhaps it's a totally thoughtless and reflexive reaction. We don't know and (spoiler alert!) we never get conclusive evidence. That is left up to the reader.

The movie versions of Solaris (there have been three) all focus on the dramatic aspect of the past's intrusion on the present, which Lem found frustrating. To him, the point of the book, like much of his other work, was to speculate on the possibility—or impossibility—of two vastly different lifeforms to communicate in any meaningful way.

It's the open-ended speculative nature of the book that makes me unsure of what to say about Solaris. This was the rare piece of fiction I immediately turned back and started reading again. I'm not ever opposed to rereading a book, but usually I have to give it a few years before I can go back and enjoy it.

But—did I like it? I...guess. I love the idea of a maybe-sentient blob creature forever beyond our understanding. There's something about the writing, though, that keeps me from really loving the book. That's why I want so much for there to be a visual version—if not movie, then graphic novel. It's such a poetic and thought-provoking idea, but ultimately it feels trapped in the language and aesthetics of mid-century science fiction. This is a far different kettle of fish than, say, Philip K. Dick.

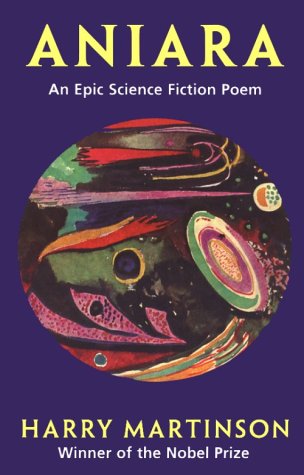

In fact, the one piece of comparable science fiction that came to mind when writing this review was Harry Martinson's Aniara. I say comparable, even though at first blush they are not particularly similar aside from being space-oriented science fiction written by European writers in the middle of the 20th century: Aniara is a series of poems about the fictional future spaceship, the Aniara, which was originally intended for Mars but instead became cast adrift into the space beyond our solar system. What holds them together for me is that they are not content to be mere diversions, entertainment; Lem and Martinson, in very different ways, use the same genre as a stepping stone towards a greater statement, maybe even art (whatever that is).

Did I enjoy either of them in the same way that I enjoy other pieces of science fiction, like Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? or Light? No. Definitely not. But worth reading? Yes. Will it challenge you? Without a doubt.

No comments:

Post a Comment